Blog

Blog

Flow Theory and Experiences

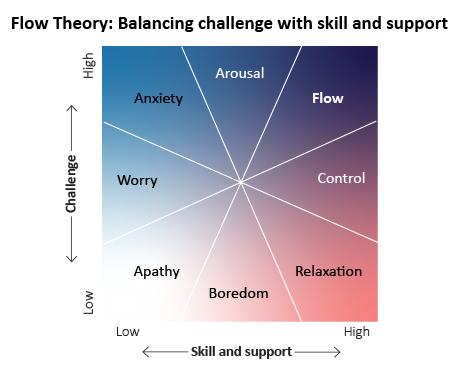

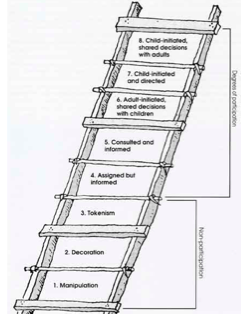

Our name, Flow Associates, is in honour of ‘flow theory’ created by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, who died last month aged 87. He was a Hungarian-American psychology professor, interested in mental states for creativity and productivity. He wrote the book Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience after 10 years of international research. The core theory can be explained with this diagram below, which shows the different mental states around the flow state, which can be achieved with the right balance of challenge and skill. It shows that the opposite of flow is apathy – not wanting to engage at all.

I founded Flow Associates in 2006, when I realised that I can’t work full time within an institution. I work very well when I am intrinsically motivated and free to do it in my own way, but I become very stressed when working under conditions set by other people. I need to spend plenty of time doing activities that get me into a flow state, such as drawing from my imagination, expressive dancing and singing.

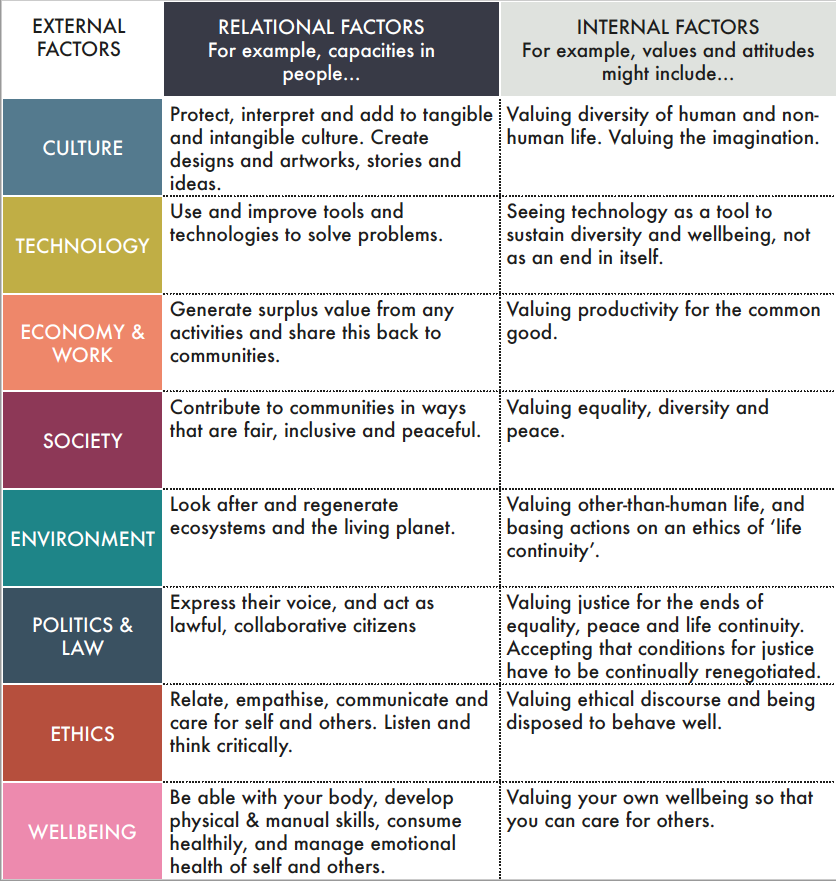

I was reading this book at the time of founding Flow, so the company naming was partly about timing and chance. But, the theory does guide us. For example, we (myself, Susanne Buck and Alex Flowers) always make sure to choose work we are challenged by, and that we are equipped to do. We particularly enjoy projects where outcomes for people develop:

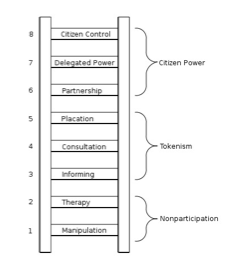

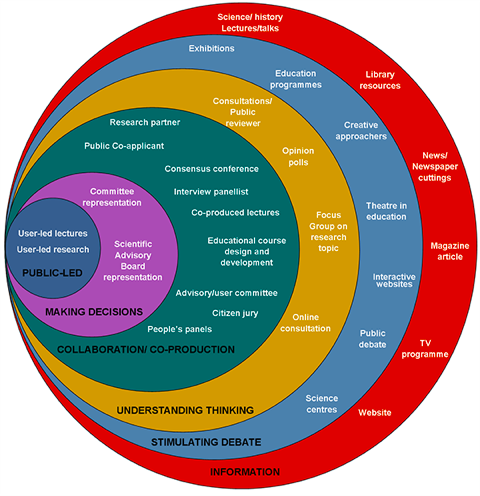

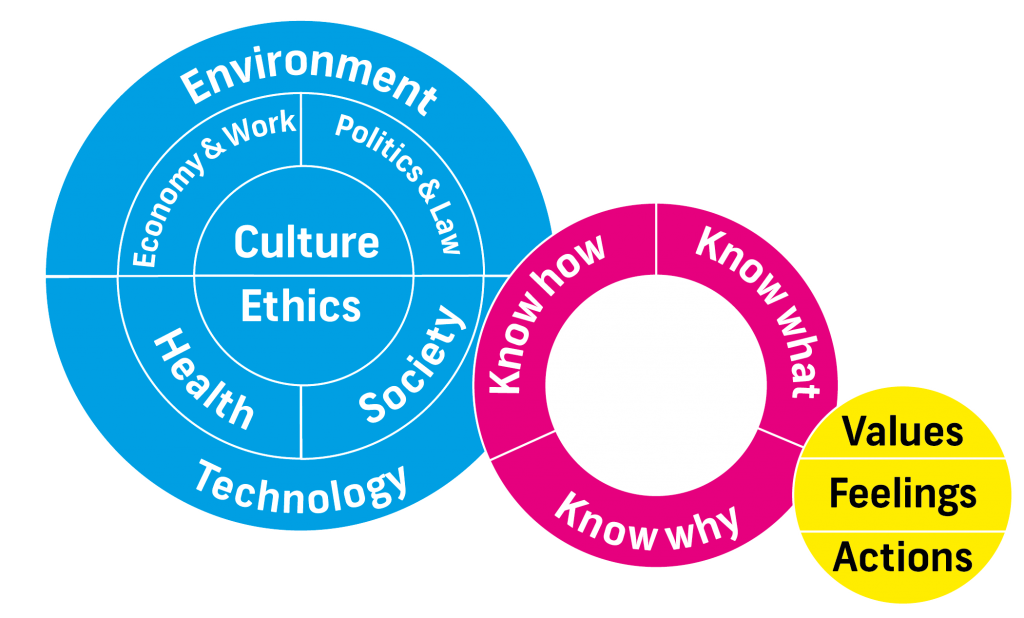

- Their sense of agency to effect change in their world

- Capacities of knowledge, skill and meaning-making

- Positive and compassionate values and behaviours.

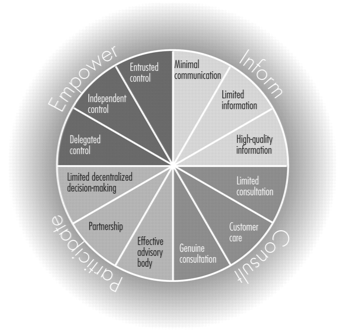

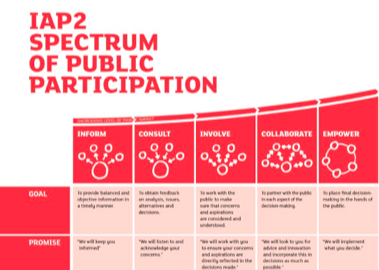

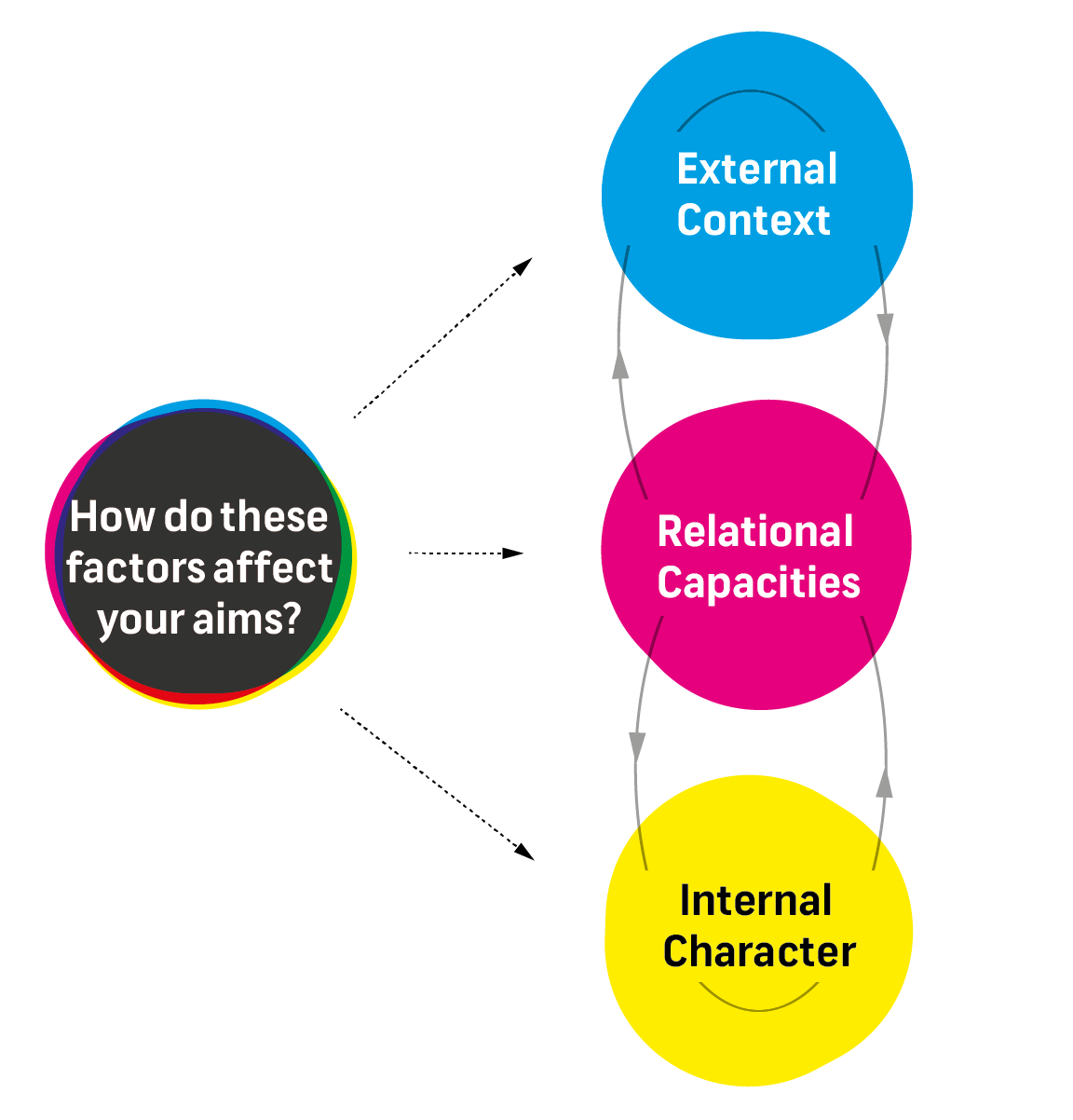

Flow theory hinges on the development of capacities, and how conditions can be designed to enable people to achieve their full potential. This thinking can apply to all the people we might work with, whether staff in client organisations or their audiences. It isn’t the only theory we use, and our thinking is growing all the time, but flow theory offers a basic and motivating concept to help anyone designing experiences and services that will engage people and develop their capacities.

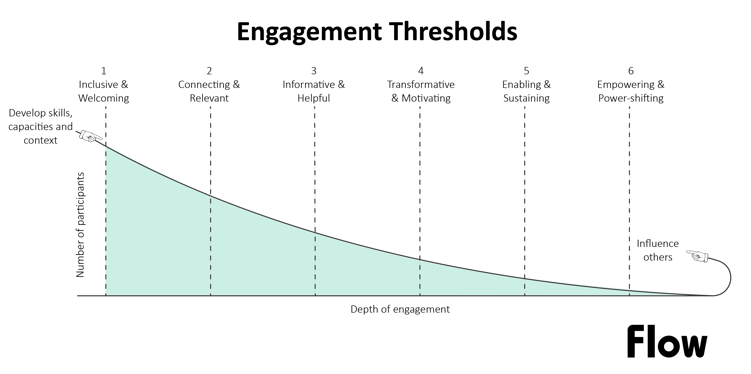

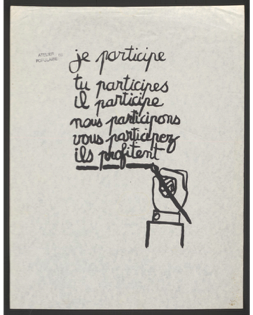

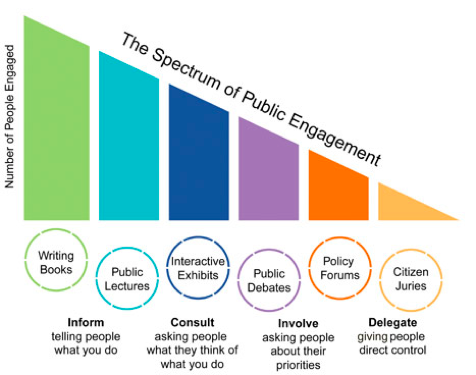

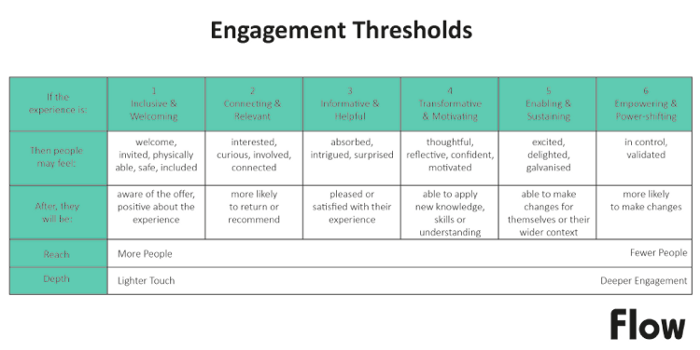

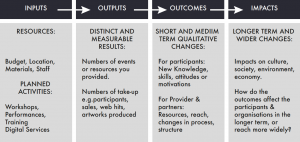

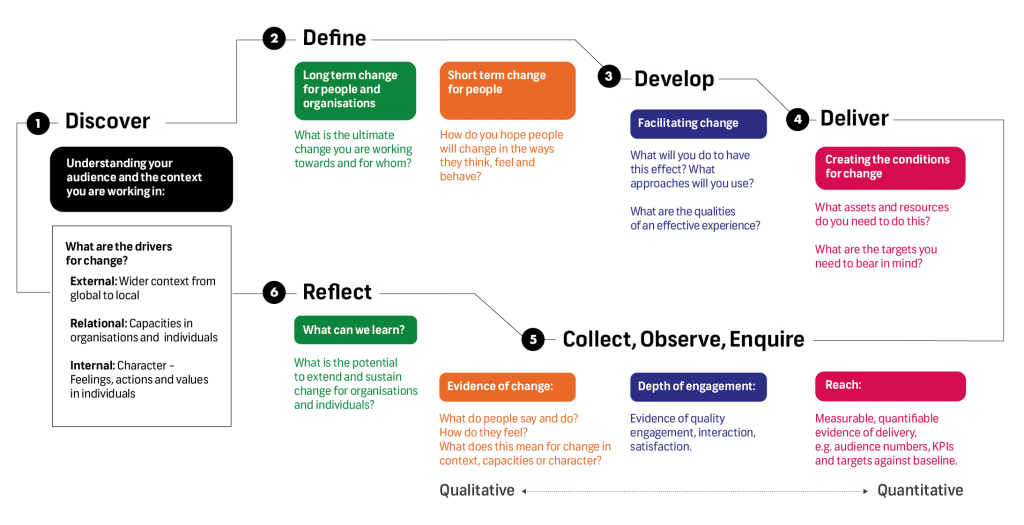

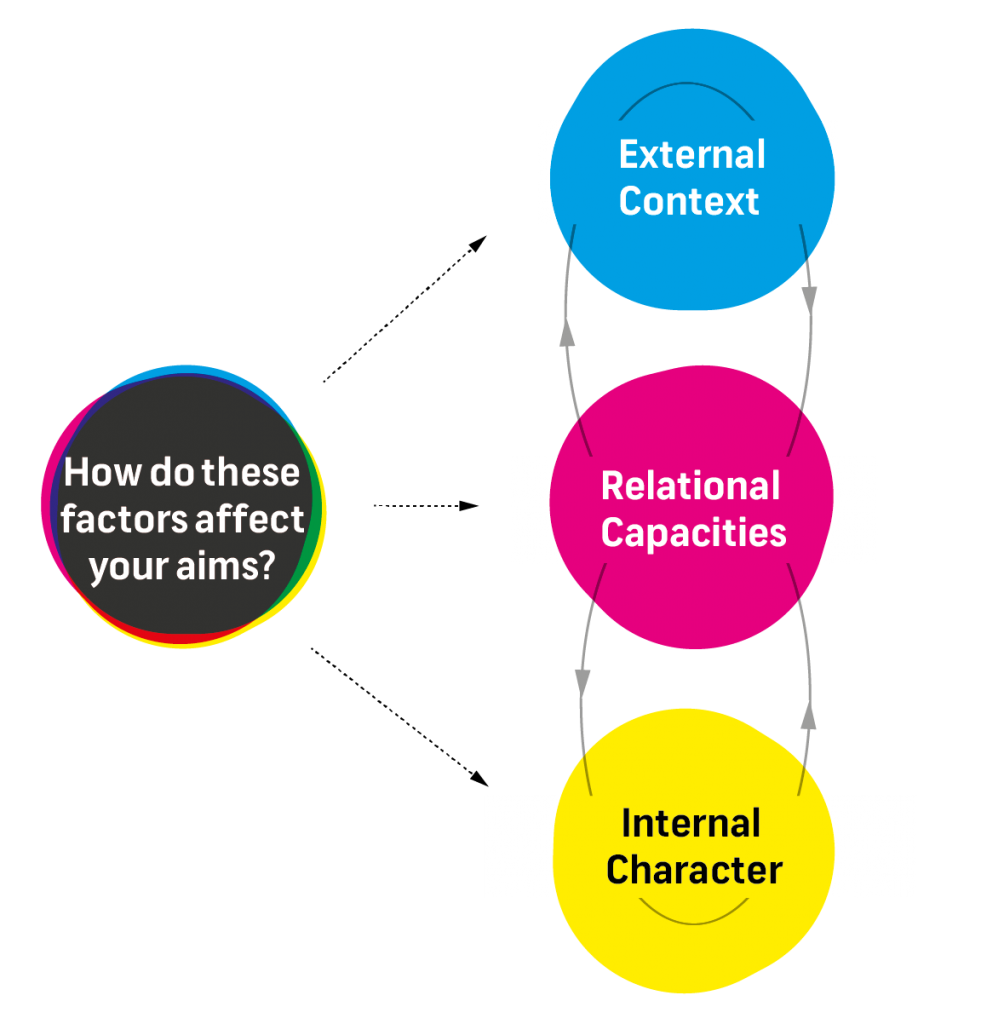

Flow theory lies behind our Engagement model, as we view engagement as more than boosting numbers or reaching certain groups of people. What matters most is the impact that this engagement has on people and communities. As people pass through each threshold they develop their skills and abilities to improve or cope with their context. If any activities intended to engage people are not designed with some components of flow theory in mind, they are less likely to succeed.

This article goes into more detail into the nine components to achieving the flow state, to provide inspiration for designing successful experiences.

The best known is achieving a good balance of challenge and skill. Enough challenge might mean that the activity offers lots of room to keep improving skills, or to be creative with its forms. Good enough skills might mean having resources or the right place, time to practice, confidence, dexterity or knowledge. Without enough challenge you become bored, and without enough skills, you will become anxious. I used to be very anxious about painting because I got the lowest possible mark for my A level Art exam, but I have found methods and materials that suit me so that I can get into flow when doing it.

The merging of action and awareness is all about learning through doing. It’s about laying down muscle memory through thoughtful practice. Doing could include speaking, writing or thinking with others, not just acting with your hands and body. It involves a balance of just enough action and just enough reflection on what you are doing. If you overthink you will get stuck, and if you rush at action without checking on yourself, you will struggle to do a good job.

Clarity of goals might seem an obvious one. However, you need to approach this the right way. If your goals are too limited and closed, or too unachievable, you will lose motivation. A good goal might look like “I will build a chair that my children will want to sit in, and it will be safe for them”. You might not know how to do it, but you have the tools, and this is where the exciting challenge lies. A less clear goal would be “I fancy building a chair like a rocket that rocks and spins around.” If you start with the goal to build a safe, attractive thing for a defined user, you can still shape it like a rocket and add fun features, but you have to ground the goal in real needs.

Immediate and unambiguous feedback is related to component number 2, the merging of action and awareness. But this is particularly about ensuring you get feedback from others and think of their views. Imagine you’re a costume designer for a big themed event. You can enjoy the creative process on your own but you have to ask the opinions of your clients and co-workers, at the right time, to be able to keep moving on in your task. These voices can tell you what you need to know, especially if you ask clear questions: will people want to wear the costumes? Do they fit the theme? Will they bring the right balance of humour and elegance?

Concentration on the task at hand is all about creating the right conditions for focus. This might mean creating a defined space or time for an experience, or removing distractions and deciding to tackle only one task at a time. It’s a basic practical component, but one that can be quite hard to achieve. Some people are much better than others at blocking out all disturbances to focus – and this is very likely to be because they are highly motivated by their chosen activity.

Paradox of control is a really fascinating component. Have you ever tried something like dancing and singing at the same time? If you are too conscious of all the steps and lyrics, and are determined to stick to the exact routine, you are in control. BUT, you will feel tight and are likely to stumble or forget your place. If you tell yourself that it’s OK to lose your place, and let the sense of enjoyment take over, you can move more towards a state of arousal. But if you aren’t in control of your routine, you might improvise too much and lose it all. It’s a paradox. So, what works is a constant pulsing of letting go and coming back to the plan, letting go to enjoy yourself, and back to the plan.

Transformation of time is all about how when you’re in flow you don’t notice the time passing. You’re not thinking about when you can have a break or what else is on your To Do list. You’re not worrying about something in the past. Without those two markers of the past and future as barriers in your mind, you can immerse yourself in the process of the moment. I go to an expressive dancing class for three hours on Saturdays, and the time goes by in a flash, whereas if I spent three hours running it would feel like 12 hours instead!

Loss of self-consciousness is very similar to losing track of time. You might lose a sense of embarrassment. You might stop worrying about an issue that has been preoccupying you. You might not think about your appearance or what others need from you. You almost become the task, or the experience, for a while.

Autotelic experience is all about enjoying an experience for its own sake, because it’s enjoyable or fulfils people’s own intrinsic needs, rather than being required or expected from outside (or extrinsic) demands. Some people can be more autotelic than others. Autotelic means self-motivated. Autotelic people don’t need to be rewarded, as they find their own rewards in their chosen activities, and they might refuse to do activities they don’t enjoy. A well designed experience is autotelic, and also encourages people to find experiences for themselves where they can feel the same again. Good experiences might create more autotelic people – which can be a challenge to our society if education or work requires people to do things they don’t want to do. And then again, if there are more autotelic people, education and work will have to change to accommodate their highly motivated personalities!

What have you taken from this set of components? Can any be useful for you in your role, or in the design of experiences that really engage people?